- Home

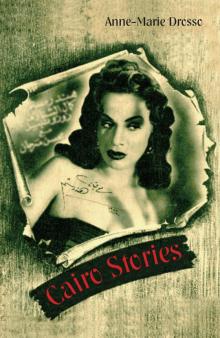

- Anne-Marie Drosso

Cairo Stories

Cairo Stories Read online

Anne-Marie Drosso

Cairo Stories

TELEGRAM

eISBN 13: 978-1-84659-105-1

Copyright © Anne-Marie Drosso 2007 and 2011

First published in 2007 by Telegram Books

This eBook edition published 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

TELEGRAM

26 Westbourne Grove, London W2 5RH

www.telegrambooks.com

Contents

Twist

Flight to Marsa Matruh

From Alexandria to Roseville

Other Worlds; Other Times (Racy Subjects)

Meant for Each Other

Penance

Hand on Heart

Pasha, Be Careful

Heat

They Took Everything

Fracture

Turbulence

Next on the List?

He has Aged

I Want These Pills

Egyptians Who Cannot Fill in a Form in Arabic

Glossary

Voices

Ideal and dearly beloved voices

of those who are dead, or of those

who are lost to us like the dead.

Sometimes they speak to us in our dreams;

sometimes in thought the mind hears them.

And for a moment with their echo other echoes

return from the first poetry of our lives –

like music that extinguishes the far-off night.

CP Cavafy

from The Complete Poems of Cavafy (Harvard, 1976)

Twist

‘Come on, let’s twist again, like we did last summer …’ The girl, big for her age (she was turning eleven soon) had turned on the radio, almost full blast. Her father, far too old really to be her father, and perhaps for that reason much more indulgent than most, didn’t seem to mind. In fact, the tune brought a half-smile to his face. Or was it the girl’s vigorous twisting and turning to the music that cheered him up?

Studying her movements as best she could, in a long but narrow decorative mirror that hung in the living room, the girl had an idea. She could improve her twist by practising with the Hula-Hoop, which her mother had put away (she didn’t want her using it in the apartment, for it could go flying and shatter pictures, lamps, mirrors, ceramic bowls, Chinese vases, glass ashtrays, silver jugs, Turkish trays or any number of knick-knacks – all objects to which the mother was far too attached, as far as the girl was concerned). A vase had been shattered in the past, and her mother, while restrained, had declared, with what sounded like absolute finality, that the Hula-Hoop was meant for the club and the club only, and was never to be used in the apartment.

The girl looked at her father, who was looking at her, and said, ‘I think I‘d dance much better if I could practice, just a little bit, with the Hula-Hoop. Please!’

‘Just be careful,’ he replied with evident complicity.

The mother was out for the evening. The old father and the little-but-big girl were on their own. They were both in the living room. The girl’s schoolbooks and copybooks were scattered on a large table in the adjoining dining room – a mess that would have to be tidied up before the mother returned. The table was large enough to be used as a ping-pong table whenever the girl’s friends visited. Lined up in the middle of the table, hardback books would serve as the net. Leather-bound books worked particularly well, but some of those were off-limits. The mother didn’t seem to mind seeing the dining room transformed into a ping-pong room, as long as books she considered special were left alone. However, use of the Hula-Hoop at home she most definitely minded.

‘Come on, let’s twist again, like we did last summer …’ Humming the tune, the girl was now twisting with the Hula-Hoop around her. The summer was gone. It had been an unusually mild summer in Cairo and all of Egypt; the summer of her falling hopelessly in love with a fourteen-year old boy who had only a marginal interest in her. She had resigned herself to that but still thought about him and about what might have happened, had he reciprocated her love. He had held her hand twice at the club’s open-air cinema. And had given her a kiss once. But that was all.

It was late fall now. The evenings were all of a sudden quite cool. Big, old Cairene apartments tend to be draughty and cold in the wintertime, requiring one to wear woollen sweaters. It hadn’t quite reached that point yet, but the girl unexpectedly shivered. Her father noticed and was alarmed, ‘Are you not feeling well?’ he asked. ‘You danced too strenuously. You ought to rest now, and then finish your homework.’

‘I’m fine,’ the girl replied impatiently. ‘Besides, I’ve finished my homework.’

‘But when? I didn’t see you return to the table,’ the father queried.

‘When you were dozing,’ she answered mischievously, knowing full well that he did not like to be reminded that he sometimes dozed in his armchair. On the coffee table right next to him there was a thick dictionary, as well as a tiny notepad and a pencil. While she did her homework in the evenings, he would bury his head in the dictionary, taking notes.

‘I just closed my eyes for a few minutes. I was a bit tired. I had been reading for too long. You are old enough to know that when people close their eyes they’re not necessarily asleep,’ he said sternly.

Just as he finished saying this, they heard the click of a key in the front door. They quickly looked at each other. Could it be that her mother was back already? So soon? The girl jumped out of the Hula-Hoop, half-hid it behind the biggest of the upholstered armchairs, ran through the living room and the other sitting room, and saw her mother standing by the front door. The girl immediately noticed something unusual about the way her mother looked. She looked distracted, tentative, as if she wasn’t entirely sure whether she belonged there, and whether she ought to step into the apartment. She didn’t look at the girl, didn’t acknowledge her.

‘Mother,’ the girl said shyly.

The father was heard asking from the living room, ‘Is that you, Aida?’

The mother didn’t answer. She stood still, the same vacant look on her face. A few seconds elapsed before she took what seemed like a reluctant step into the apartment, forgetting her key in the latch. The girl noticed the key, took it out and followed the mother, who was by now walking very slowly through the sitting room.

‘Aida?’ the father was heard saying once more, and again the mother said nothing but continued to walk as if on automatic pilot. Through the hallway, past the kitchen, then through the second hallway, and then straight into her bedroom. Without taking any of her clothes off, not even her jacket, and with her shoes still on, she first sat on her bed, then lay on it, clutching her purse in one hand and holding her forehead with the other.

She seemed to be looking at the ceiling.

For the first time, the girl noticed, really noticed, how high the ceilings were. And how intricate the work on their cornice was. She began counting the decorative indentations all along it.

‘Where am I?’ were the first words the mother uttered. ‘Where?’ she repea

ted.

Standing by the bedroom door, the girl looked stricken, yet managed to say, ‘But at home, Mother, at home.’

‘At home?’ the mother repeated, almost inaudibly.

‘Yes, in your bedroom, on your bed.’ The girl was getting frightened. When would her mother start acting normal again? She heard her father’s footsteps in the hallway and felt somewhat relieved but also nervous, for things were already complicated and she had a vague sense that his presence might complicate them even more. She couldn’t have said exactly why she felt that way.

‘Why are you in bed?’ the father asked the mother as soon as he got into the room. ‘What made you come back so much earlier than we expected?’ He sounded solicitous and troubled.

The mother ignored his questions.

‘What’s wrong, Aida?’ he asked, obviously bewildered. The girl, who was still holding the key which her mother had forgotten in the latch, exchanged a quick glance with her father, noticing that he seemed particularly old that evening, and that he also looked helpless. He looked like he could be her mother’s father.

‘Are you not feeling well?’ he asked the mother. ‘Perhaps a glass of water would help?’

‘I do have a daughter, don’t I? And she’s away, isn’t she?’ There was complete silence in the room. And then the mother continued, ‘And I have a sister, don’t I? And she is away too, isn’t she?’ She was avoiding looking in the girl’s, or in her husband’s direction. So it appeared to the girl.

‘Of course, you have a daughter who is in Europe right now, and one who is right here, by your side and, yes, your sister is in Europe, attending her daughter’s wedding,’ the father hastened to reply without quite managing to sound reassuring. He moved closer to the bed and put his hand on his wife’s forehead, presumably to check her temperature and comfort her, just the way he did when the girl was sick.

The girl stepped backwards, almost but not quite into the hallway, wondering ‘will she mention me now?’

The mother said nothing for a while. There was again utter silence in the room; the three of them appeared frozen in place. Then the mother said quizzically, ‘So my niece is getting married.’ In saying that, she reminded the girl of a child who dutifully repeats a lesson.

‘Do you want me to call the doctor?’ the father asked. The mother didn’t answer. She still seemed to be looking at the ceiling.

‘I will call him. Right now,’ he said eagerly, almost too eagerly, as though he was looking for the first opportunity to escape the room. He left abruptly, and could be heard rushing to the telephone.

The girl was left alone standing close to the door, looking at her mother, still wondering whether she would somehow acknowledge her presence.

‘Does she not remember me?’ The girl’s heart started beating wildly. ‘Does she not remember who I am? Why didn’t she mention me? Why didn’t she mention my father?’

Perhaps the mother wanted to forget them – both of them. Perhaps she wanted to live her life unencumbered, free from the two of them. Perhaps she ought to tell her mother, ‘Mother, I’m here; I am your daughter. You know that, don’t you?’ But the words would not cross her lips. She could not make herself say them. To say them would be to acknowledge the possibility that her mother no longer knew her, no longer remembered her. To think that thought was one thing, to voice it was too much, so she kept still, waiting for her mother to revert to her old self – to stop being this stranger lying, fully clothed, on the bed.

It seemed like her father would never come back. She could hear him faintly. He was whispering on the phone, so he must have reached the doctor. Her mother had closed her eyes. The girl looked down. She’d been standing barefoot on the tiles and her feet were getting cold. She rubbed them against each other. ‘Come on, let’s twist again, like we did last summer …’ The tune was back in her head. She found herself humming it softly. Then she thought she heard the call to prayer from the mosque she passed every time she walked to her aunt’s place, but wasn’t it too late in the evening for the prayer? Then the oddest question crossed her mind: would she still love her mother if her mother showed no signs of remembering her, or loving her? She might not; she might stop loving her.

She looked at her mother hard. Could it really be that she loved her only because she felt loved by her? Was this what that love was all about? What an intolerable thought! All of a sudden, the girl found herself running towards the bed where her mother lay. She knelt in front of it, laid her head on it, burying her face deep into the mattress. It didn’t take long before she felt her mother’s hand stroking her hair. ‘Now she’ll say my name,’ the girl whispered to herself, ‘now she will remember.’

Flight to Marsa Matruh

Around six in the evening, the holidaymakers would start gathering their belongings and amble back to their huts, hotel rooms and little villas to shower, have a nap, and plan outings meant to last late into the night. Often a few young men and women stayed behind on these long summer evenings, so the beach was never quite deserted. But it was rare for someone to be seen arriving at the beach then, except for parents shouting their children’s names while surveying the shore and the sea, some nervously, others with exasperation.

Marsa Matruh’s famed azure-coloured sea looked its most inviting just around that time of the evening, as the sun was about to set. Even the most prosaic of souls found themselves gripped by its shimmering surface. On their way back to their chalets and villas, men and women alike would turn round to look, one more time, at the expanse of blue, flowing into the rosy sky.

One such evening, Mrs Z., who had just arrived in Marsa Matruh intending to stay for only three days, turned up at the beach followed by a beach attendant, an adolescent carrying a folding chair. As they were approaching the sea, Mrs Z., though reserved by nature, found herself, telling the young boy, ‘Beautiful, isn’t it?’ With a proprietary air and beaming with pride the boy replied, ‘This beach is the most beautiful in the world.’ Mrs Z. smiled. In one hand she held a towel wrapped around a book and a swimming cap, and, in the other, suntan lotion. Exceedingly fair, she had the type of skin that burns easily. But to be carrying suntan lotion at that time of the day seemed excessive: it indicated an overly cautious nature.

No longer young, she still had a marvellous face, without a line or a frown – so symmetrical that those in search of exotica might have found it boring, but for admirers of classical beauty, it was a face to behold. An ivory complexion and very fine skin, the straightest and most proportionate of noses, expressive lips curling up at the corners as though hinting at a smile, honey-coloured eyes highlighted by finely arched eyebrows – all this set off by a perfectly oval face. Her wraparound beach dress, which revealed little of her shape, hinted at modesty. She appeared to be slim yet curvaceous. What betrayed a certain age were her soft upper arms, and also, her hairdo, which was rather old-fashioned, with locks of hair styled to curl around her cheeks.

When Mrs Z. pointed to a spot a few metres away from the water, the young boy ran, unfolded the chair where she wanted it, made sure it was steady and left whistling, satisfied with his tip.

Mrs Z. was not alone on the beach. A very young woman, wearing white shorts and a white top – a girl really – was taunting two young men by throwing balls of wet sand in their direction. Pretending to retaliate with yet bigger ones, though not actually throwing them, the young men visibly enjoyed the girl’s taunts. Her compact body moved like a cat, and she had a loud, sharp laugh, surprisingly loud for a person of her size. From a distance, she looked rather attractive, Mrs Z. thought, as she made herself comfortable in the folding chair, putting the book on her lap. ‘A charming sight, as long as she does not throw her sand balls anywhere close,’ was her next thought. A few seconds later, a sand ball landed at her feet.

‘See what you’ve done!’ one of the young men shouted. The girl ran to offer her apologies, which Mrs Z. accepted, saying ‘I am unfortunately too old to take part in your games. Be careful

next time,’ to which the girl replied, ‘You are not old at all; you look like a flower.’ ‘Come now, there is no need to resort to flattery. You’ve already apologised. Go and have fun with your friends. They’re waiting for you,’ Mrs Z. suggested. The girl burst out laughing and said, ‘I must go home. They’ll have to have fun without me.’ Then she walked briskly towards a path leading to a cluster of chalets, ignoring the young men’s entreaties for her to stay just a little longer.

Mrs Z. watched the shrinking, gazelle-like silhouette of the girl, who was now running. Watching her run, she became aware of a kind of longing – a longing for the freedom to do foolish and frivolous things. She could not remember a period, past her adolescence, when she had fully experienced that freedom. She had got married far too young, on an impulse. That was the worst part of it; she had only herself to blame. The marriage turned out to be thoroughly unsuitable. During the first ten years she had closed her eyes to its many shortcomings, not wanting to admit to herself, or others, that she had made a big mistake. When her pride subsided and she finally assessed the marriage for what it was, a failure, she had lacked the courage to end it and had soldiered on, barely keeping up appearances. It was a suffocating way to lead one’s life.

‘This is not a train of thought worth pursuing,’ Mrs Z. admonished herself as she opened the book on her lap. A bit of reading, then a swim. Tomorrow, she would see her youngest daughter, who was at a holiday camp in Marsa Matruh. Though immensely glad to be seeing her daughter, she was anxious about the meeting, as she suspected that the little girl would beg her to take her back home. Some children love summer camp, others do not. Unlike her other children, her youngest daughter did not seem to like camp at all. How would she handle her daughter’s pleas to go home – if it came to that? She hated having to use her authority to make people do what they did not want to do. It was not in her nature to control – or try to control – people’s lives, even her children’s lives. What would be the point of wrecking the little girl’s summer by insisting that she stay in Marsa Matruh? Because camp is supposed to be a good experience for children to have? Because she herself was the kind of person who enjoyed group activities and interaction? These did not seem like good enough reasons. She feared that she might not have the heart to leave the girl in Marsa Matruh; and yet parenting was supposed to be, in part, about toughening one’s children and, in the process, one’s own heart. Tomorrow promised to bring a set of problems she did not feel up to facing.

Cairo Stories

Cairo Stories