- Home

- Anne-Marie Drosso

Cairo Stories Page 2

Cairo Stories Read online

Page 2

For about half an hour, Mrs Z. immersed herself in her book; half an hour of pure pleasure. Then the book itself started another negative stream of thoughts with a passage that stated:

Life is not so simple. There are complications … entanglements. It cuts all ways, till – till you don’t know where you are.

She closed the book. It sounded like her life – cutting all ways ‘till you don’t know where you are’.

* * *

She had finally reached some fragile equilibrium in her marriage. Her husband had come to accept the attentions heaped upon her by her many admirers. His jealous outbursts were fewer and more short-lived. Not so long ago, in the course of a painful exchange, she had tried to explain to him that it was not love that tied her to the gentleman who had come to feature so heavily in her life. A certain affection, yes, and also gratitude for his attentions, but not love. While far from being a proponent of telling the truth at all times and at any cost, this time she had thought it important to let her husband know where she stood.

The gentleman himself she had done her best not to mislead. She had never told him that she loved him. She had offered him her friendship, and a little more, but, most of all, she had offered him a warm and understanding ear. Profoundly unhappy in his marriage, her lover was not as resigned to his unhappiness as she seemed to be to hers. She would listen to him express his anger at being tied to a marriage he had lost all interest in, and, as was typical of her, would counsel equanimity. Sometimes she even defended his wife. Her manner with him was always warm and serene, never demanding. In fact he wished that she would be more demanding of his time and attention, instead of just taking what he offered. He tried to convince himself that her reserve was because he was married, and, if he were free, she would be more demonstrative. But he sensed that the distance she maintained between them was insurmountable, that it reflected the way she felt about him. Whenever he had the courage to face up to that, he despaired, since she had come to symbolise for him a promise of happiness, however illusory. By listening to him as she did – with discernment, tact and without judgement – she had become his lifeline. They were both aware of that.

‘And, so where am I at now?’ Mrs Z. wondered, knowing the question to be silly and self-indulgent. She was in Marsa Matruh without her husband – and without Mr A. She was certain that her husband believed her to be in Marsa Matruh with Mr A. She had not disabused him of that idea, as she suspected that he would dread infinitely more the thought of her being there on her own than with Mr A., whose presence in her life he had come to tolerate to some extent. The knowledge that she was there on her own would lead him to imagine all sorts of things. He would be imagining that she might fall in love – really in love, this time.

So that was what it had come to: her husband finding Mr A.’s presence by her side reassuring, for he had chosen to believe her when she had revealed to him how she felt about the gentleman. It had not extinguished his jealousy, but it had tempered it. It occurred to her that, once back home, she would have to preserve her husband’s impression that she had gone to Marsa Matruh with Mr A. – in a roundabout way of course since, when it came to such matters, she resorted to euphemisms to spare his pride.

Mr A. was not with her because she had wanted to be by herself in Marsa Matruh. It was as simple as that, but neither man would understand this. She recalled an awkward telephone conversation with Mr A., how she had been driven to tell him a white lie about her going. She had called to say that she would be going to check on how things were going for her little girl: ‘Wonderful! I’ll book a room at the Beau Site with full sea view. I’ll say that I’m tied up with a business trip,’ he declared enthusiastically.

She replied as firmly as she could: ‘Well, I think it would be preferable for me to go by myself.’

‘By yourself?’ he exclaimed without giving her time to say anything else, and then, with a faltering voice, ‘But why? Why?’

‘To spend time with the little one.’

Sounding more upbeat, he countered, ‘But you will have plenty of time. Mornings; afternoons; as you please. I’ll be accommodating, you’ll see.’

It was then that she felt compelled to tell her white lie: ‘The truth is that my husband would take it very much to heart were he to find out that you came along, and that the little one found out about it. I don’t want a big scene. I don’t feel up to it. Besides, it’s understandable that he’d get upset. The trip is meant to be for the little one. Surely you understand that?’

After a heavy silence, her lover proposed, with discernible diffidence, ‘I may have a solution. What if I book myself a room in another hotel? Will that do?’

‘I don’t think so,’ she replied. ‘You know these resorts; it’s hard to escape attention.’

‘But to go by yourself makes no sense, no sense whatsoever when it would be so easy for us to be together!’ he almost shouted.

‘Be reasonable.’ she replied, getting upset.

‘I’m trying to be.’ he said, so despondently that she briefly considered giving way but, in the end, stuck to her initial decision.

The conversation ended with his saying that he would book the room for her. Would she please allow him to do that? It would make him feel part of her little excursion.

She had let him make all the necessary arrangements, and, up until she left for Marsa Matruh, had had to endure his dejected tone whenever they spoke on the phone or met. It was clear that part of him was still hoping that she would change her mind and let him join her. He went so far as to write her a letter, complaining that she guarded her independence with such vigilance that it caused those who loved her to feel cut off from her. Would she forgive him for loving her as much as he did? The tone suggested that he might have guessed that she had used her husband as an excuse. She thanked him for the letter without referring to its contents.

In sum, she had used her husband to try to pacify her lover, and was using her lover to try to pacify her husband. That was where she was at – not a good place to be.

‘Always equivocating’, a friend once said affectionately of her at an intimate gathering where the guests were asked to describe each others’ characters. And he had added, half-seriously, ‘Here, even her smile is slightly equivocal,’ which had made people laugh. She too had laughed, as there was no doubt in her mind that the remarks were well-intentioned. Her friends liked her a lot – all of them did: that was unequivocal. She derived a great deal of comfort from that knowledge.

* * *

As Mrs Z.’s thoughts turned this way and that, the sun set and a small breeze could be felt. Years and years earlier, a man had made her appreciate nature and the outdoors in ways she had never experienced before, and never would experience after he ceased to be a part of her life. Him she had loved. She sighed a very small sigh. She was almost fifty years old, still made some men’s hearts beat, was still the object of jealousy and desire and yet, instead of deriving pleasure from this, she felt it was all in vain. Futility was the title of the book resting on her lap – a title that seemed to capture her assessment of much of her life at this point in time.

There would be a dance at the hotel later in the evening; it was Saturday night. Mr A. had let her know – not too subtly – that he would mind her going to the dance. She had had no intention of going, although she rather enjoyed dancing, even if by her standards she wasn’t too good at it. Yet she refused to promise him not to go. She did not want to give up the little bit of freedom she had carved for herself in a life she had come to experience as a web of confining ties and obligations and false gestures.

‘Enough of these pointless thoughts,’ she decided, getting up more energetically than was usual for her. She removed her dress, revealing an austere but flattering black swimsuit that provided a sharp contrast to her soft, fair skin. Adjusting her swimming cap, she walked towards the beach. When she reached the water she dipped her toes in, took a few steps, then, after standing still for a few secon

ds, walked in more resolutely and gently dived.

Mrs Z. was a methodical swimmer. Her favourite stroke was the crawl. From the way she swam it was evident that she was conscious of style and worked hard to do it right. Speed was not her objective. She was in fact quite a slow but tenacious swimmer, with a meticulous stroke despite her weak kicks. When on her own she stayed close to the shore. That evening she ventured reasonably far from the shore, and also swam for a long time – an hour or so – until it was almost dark.

Back on the beach, she looked around. The two young men, whose games with the girl had amused her, were gone. An older man walking with a stoop, his hands behind his back, was the only person to be seen, in addition to the young beach attendant who was playing with an abandoned, slightly deflated beach balloon. She had returned from her swim with the firm intent of taking her little girl back home, if the girl seemed miserable. She would not let her languish at camp.

At the intimate, old-fashioned hotel she was told by the receptionist that two telegrams were waiting for her. One from Mr A.: ‘Am so tempted to join you – if only for a day. Call me at the office, if it is a “yes”!’ and one from her husband: ‘I hope that you and the little one are having a wonderful time. I miss you both!’

‘I hope it’s only good news,’ the receptionist said.

‘Yes, it’s good news,’ she answered, forcing herself to smile.

‘Thank God!’ he said.

‘Thank God,’ she repeated after him, then walked towards the stairs leading to her room, sorely tempted to crumple the pieces of paper in her hands and throw them away; she just crumpled them.

‘Hilda, what a wonderful surprise!’ she heard a man exclaim happily. It was a familiar voice. Could it be Max? It was, and just around the corner was Lola, his wife, equally happy to see her. They hugged and kissed. She was pleased to see them, welcoming any distraction. It so happened that she liked them – both of them. Max had once been rather in love with her, which had not stopped Lola from becoming a good friend over the years. There was not an ounce of jealousy between the two women.

‘You must come to the dance,’ Lola declared.

‘I’m a bit tired,’ she answered. ‘Tomorrow I have to get up very early to have breakfast with the little one: she’s not happy at camp.’

‘Hilda, you must come; no ifs or buts; Rafiq will be there. He’s on his own. I can’t dance with both Max and Rafiq, so we definitely need you.’

‘We do,’ Max said, putting his arm around her shoulders.

Mrs Z. knew of Lola’s soft spot for Rafiq. She smiled, ‘I’ll do my best.’

Lola replied, beaming, ‘We count on you. Don’t let us down.’

A petite woman, with average features, Lola had what people call sex appeal. It was the way she moved but also the way she flirted with everybody, men, women and children alike – a trait admired by Mrs Z., to whom flirting did not come easily. Lola’s effervescence was catching. By the time she left them, Mrs Z. felt almost cheerful. ‘What a fortuitous meeting,’ she thought. Then, ‘Why should I skip the dance? Why while away the evening by myself, moping about things that can’t be changed?’

Once in her room she examined the clothes she had brought, noting the absence of a party dress; she had not planned on going out in the evening. However, she was not fussy about clothes, so that was not an issue. She put on a simple, straight black skirt which, like all her skirts, just covered her knees – a part of the female anatomy she found best hidden. And, to go with it, she chose a V-neck sweater made of very soft cotton – so soft it could pass for silk. Its rich green colour was especially becoming, as it highlighted her honey-coloured eyes. Black, high-heeled sandals with a fine strap gave the ensemble a dressy look. Just before leaving the room, she clasped a subdued necklace made of false pearls around her neck, quickly looked at herself in the mirror, judged the necklace to be appropriately understated, and hurried out of the room just as the phone rang.

The evening proved to be thoroughly enjoyable. The band was keen on the cha-cha-cha, a dance she danced well, though she did have to concentrate on the steps. She danced both with Max and with Rafiq. Not once did her mind wander to the subjects that had preoccupied her earlier in the evening. Even Max asking her, with solicitude, ‘How are things going?’ (he knew vaguely about the odd arrangements in her life) did not re-ignite her blue mood. She was determined to enjoy the evening. She answered Max’s question with an evasive ‘Quite alright.’

On her way back to her room, around midnight, she passed reception and heard the receptionist call, ‘Madam’. There had been two phone calls for her. The gentleman handed her a folded piece of paper bearing the names of the callers. She put the piece of paper in her bag without bothering to unfold it.

In bed, she tried to read before going to sleep but couldn’t concentrate. It was rare for her not to be able to concentrate. This whole situation had finally got on top of her. She could not help feeling she was betraying both men when, most of all, it was herself she was betraying. People assumed that she had always been the equivocating person she had become, accepting of all sorts of situations, open to any compromise. Yet, there was a time when she had been steadfast, daring, determined, even headstrong. Marrying the man she had married – in defiance of family and friends – attested to that.

She would write to both men tomorrow, telling them that the present situation could not go on. She had planned on an early-morning swim before going to see her daughter, but she would skip the swim and write those letters. Neither the marriage, nor the other relationship, made any sense. Neither was suitable. Neither was fulfilling. She began to compose the letters in her head, already dreading the consequences of sending them. Then, in the end, she fell asleep. But not soundly: every so often she woke up, tormented by the thought of how to explain to the two men, without hurting them too much, that she could no longer endure the present situation. But what was it exactly she could not endure? The tepidness of her own feelings? The constraints on her behaviour?

Very early in the morning, the phone rang. It was Mr A. – all apologetic. Yes, he had called her the previous evening, which was a foolish thing to do as she must have gone to the dance. It would have been a pity for her not to go. She deserved to have some fun. He was glad that she went, and felt immensely stupid for having suggested otherwise. Was the company pleasant, the band any good, the conversation interesting?

A few minutes after she put the receiver down the phone rang again. It was her husband. ‘I hope that I am not disturbing you too early – but I wanted to remind you to treat the little one to an ice cream on my behalf. You know how much she loves ice creams! I’ll let you go now. I know you’re busy. Enjoy the rest of the weekend. It’s dull here without you.’

* * *

The two phone calls revived Mrs Z.’s original plan to go for an early-morning swim. ‘I must go for a swim, or I’ll go mad,’ she told herself, though she did not usually think in hyperbole. She hastily put on her swimsuit and wraparound beach dress, grabbed her swimming cap and was about to reach for the suntan lotion but changed her mind. It was not yet 7.30 in the morning. Besides, so what if a little bit of sun shone on her face!

Later, when she had calmed down in the water, words uttered by the man she had loved years earlier rang in her ears, ‘It’s touching to see you swim. You try so hard to do it right. It’s so much like you; always trying hard to do it right.’ Why had she lacked that sort of determination when it had come to their relationship? Why had she not followed her heart? She had no children then. Her excuses had been the difficulty of leaving a husband who had little but her left, and of upsetting the life of an ailing mother, whose fate was tied to hers – all in all, good, solid excuses. But, at bottom, something else had held her back, and it had nothing to do with selflessness, generosity of heart, guilt feelings, or filial devotion. She had loved the man and been loved in return, yet had been cursed with some ingrained scepticism about the permanence of such feelings. She ha

d feared that the love would wane. This is what had immobilised her. In the end, it had seemed both cruel and senseless for her to be upsetting other people’s lives – turning these lives upside down – for something that was likely to pass, namely, love. The day would come when her lover would be noticing other women, and she other men. And, even if that were not to happen, the day would come when they would take each other’s love for granted, and show signs of tiring of each other. No amount of her doing it right would preserve their love the way she loved it.

This sense of foreboding had not been entirely speculative. One day, while discussing how to bring their lives together, he had seemed burdened by the complications involved. There had been a slight change in the tone of his voice of which he himself had been probably unaware. The change had not escaped her, giving her what she took to be a glimpse of the limits of his love. She had immediately felt her heart sinking and hardening. So she had slowly backed out of his life, letting him and the world think that family pressures had got the better of her.

Arriving at the beach, Mrs Z. set herself the target of swimming for a good forty-five minutes but, once in the water, she decided to take it easy. She turned on her back, letting herself float, the early-morning sun shining on her unprotected face. She tried to do some backstrokes but was, as always, hopeless at it.

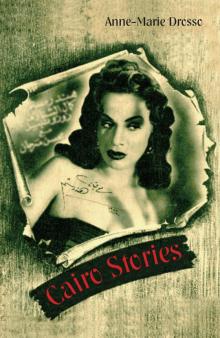

Cairo Stories

Cairo Stories