- Home

- Anne-Marie Drosso

Cairo Stories Page 3

Cairo Stories Read online

Page 3

It was time to return to the hotel. She would probably be late for the camp breakfast but, if she rushed, she might arrive before the end. She slowly swam back to the shore, making sure not to lift her head too high whenever she turned it sideways to take a breath. She wondered if the little one had made any progress mastering the crawl. Last time she had seen her swim, her strokes had been out of synch with her kicks. Was she really prepared to take the little one back home, if the girl begged her to? Now she was not so sure.

On the way to the hotel, she turned around to look at the sea. The splendour of the scenery – sky, sea and sand – left her feeling completely alone.

From Alexandria to Roseville

Paris checked his e-mail first thing that morning, and was surprised to find a message from Dr Jones.

The message read:

Dear Mr Dimitri,

I’ve just finished reading your father’s extraordinary letter which, I gather, he must have given you not long after you had faxed me your notes. It would seem that you no longer need to see me. Should I cancel your appointment? If so, the fee would just be for the initial consultation. I’ll be sending you a summary report based on the discussion we had, your notes and your father’s letter.

If you think you still need to talk, I’ll see you as scheduled on the 15th.

Having worked for over twenty years with old people, I must tell you that your father’s circumstances and reaction stand out. By all means, if it at all appeals to you, accept his invitation.

Sincerely yours,

Dr Anthony Jones

Paris replied immediately:

Dear Dr Jones,

I would like to keep the appointment. While the crisis seems to have passed, I think I would benefit from one more consultation.

See you on the 15th.

Sincerely,

Paris

To his friend Peter, he wrote:

Peter,

I owe you many thanks for suggesting I contact your psychologist friend. It went well. I, who was initially reluctant to seek a professional opinion, am now insisting on seeing more of him!

Cheers,

Paris

P.S. How about a game of golf tomorrow afternoon?

Next, instead of looking at his other e-mails, Paris pulled out, from a file lying on top of his desk, the semi-autobiographical account he had written for Dr Jones, as well as his father’s letter; he made himself comfortable and proceeded to re-read them.

* * *

Paris Notes for Dr Jones

Dear Dr Jones,

You suggested I jot down my thoughts about the situation and give you as much information about my father and myself as may be relevant. I spent a Sunday morning doing just that. I’m sure there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to my notes but I didn’t think it necessary to edit them. It is probably best to let you sift through them yourself.

Sunny Homes is in Roseville, a twenty-minute drive from St Paul, where I live and work. It is the old people’s home in which my seventy-two-year-old father now resides. It has a more homey feel than most old people’s homes I’ve checked, but then I may not be entirely impartial since I chose it for him.

I grew up in Toronto, took a law degree in Montreal, then an MBA at Stanford and have been working for a publishing house in St Paul for just over five years. I am not married but have a partner – a social worker who lives in New York. We try to see each other at least twice a month. She comes to St Paul more often than I go to New York. Our friends wonder why. ‘New York has so much more to offer,’ they remark, more often than I care to hear. The fact is that I work long hours – often even on Saturdays. While Sharon also works hard, she’s managed, thus far, to keep her weekends free. That’s why mostly she comes to me. Besides, though outwardly calm, I really am an anxious traveller. I don’t know how much longer Sharon will want to come and go, as often as she has been since we met at a friend’s place in New York four years ago. Nor do I know what I’ll do the day she decides that she has done her fair share of keeping the relationship going, and that it’s now my turn. I want to think that I’ll reciprocate, should it come to that. I’m very attached to her; we get along remarkably well. However, I’m set in my ways and tend to be compulsive about my work; thus, all in all, I am, I suppose, rather self-absorbed, as each one of my previous partners concluded after the first glow of our infatuation with each other had dimmed. Sharon may think so too, but has yet to say it.

As self-absorbed as I may be, the subject of my father’s adjustment to Sunny Homes – or rather his failure to adjust to it – has been preying on my mind. It’s only natural since he is my father, and I’m the one who suggested that he come to Roseville and move into that home – a move that required him to cross oceans; he came all the way from London, his place of residence for the previous twenty years. He has a combination of arthritis and gout that can be totally crippling and is the reason why I suggested he move to Sunny Homes, but, during periods of remission, he feels almost normal. He has sunk into a state of quasi-muteness since he moved to Sunny Homes two months ago. He’ll say very little to me when I visit him. And the staff tell me that he says virtually nothing to them, and doesn’t interact with the other residents. At the very outset – the first couple of days – he seemed willing to engage, then something snapped, and he stopped talking. He’ll say ‘thank you’ and ‘please’, but no more than that. He spends his time either in his one-bedroom apartment or – if it’s nice enough – smoking on the porch. He does go down to the dining-room for lunch and dinner (he usually skips breakfast) but looks so remote that none of the residents will sit with him. He went out once to check the Roseville library and never went back after that one time, though it isn’t a bad library. It has much more than one would expect a library in Roseville to have. I thought that he would become one of its most assiduous users.

I suppose his case is not so unusual. An elderly gentleman, with sudden health problems, moves into an old people’s home, in unfamiliar surroundings, and sinks into a blue funk. Still, I would never have anticipated that he would become so depressed that talking would get to be too much of an effort for him.

I tried to have him open up a bit and to draw him into a discussion of why he refuses to talk. Each time I tried, he smiled benignly and would not respond. Part of my problem is that I don’t know him well. I don’t know him the way a son normally knows his father. I have never lived, nor spent extended periods, with him. He and my mother were married for only a few months. They were already separated by the time I was born.

They met in the late sixties in Paris, where she was working for a publishing house. He was, by then, a successful translator of fiction and poetry, from Greek, Arabic and Russian into French, as well as into English; and from English into French, and French into English. I find it hard to believe that someone could master all these languages, three of which are very difficult. Occasionally, one hears of men and women who do, but they seem to be a thing of the past, to belong to a different era – like him, who was born in Egypt, in the mid-thirties.

Very soon after they were married – they married on the spur of the moment – my mother concluded that he was impossible to live with. He was, she used to tell me with obvious fondness, an incurable eccentric who balked at having any possessions, including cups, dishes, furniture, linen, even a bicycle, let alone a car. A true Spartan, living in and off books, with subjects of interest bordering on the obsessive, in which he would immerse himself to the exclusion of everything else. His ethereal nature had initially attracted her to him until she saw, she said, its flip-side – a lack of social know-how coupled with a disconcerting detachment; and yet, despite his apparent disinterest in personal interaction, he would astonish her by sometimes having flashes of insight about people and situations.

They remained friends after she had left him. Within two years of her leaving, she was working in New York where she met and married Greg, the man whom I would come to regard as my father

, and with whom she moved to Toronto. Greg was Canadian, she American. As for my father, who lived, intermittently, in Paris, Athens, London, and New York, where he gained American citizenship, he always kept in touch with us. Perhaps he is not quite so detached a person as my mother portrayed him. But then, he may simply be a stickler for rituals. In any case, he would send us cards, send me birthday presents, would often call us, and over the years he stayed with us in Toronto several times. They were all short stays, even though Greg, who was fond of him, made him feel welcome, and the house in which we lived had ample room for visitors. My mother treated him with the sort of protective – slightly interfering – affection I expect sisters treat younger brothers; he did not seem to mind that, which I have always found hard to understand as he was, and still is, a very private man.

My first memory of him dates back to when I was around five years old – the memory of a man with spindly legs and a crop of bushy dark hair. Unlike Greg, who was of medium height and square, my father was tall and lanky. Paradoxically, I am built more like Greg than like him. My father still has a lot of hair, but it has gone all white, and he has developed a stoop so no longer seems so tall. I remember my mother telling me, before that first visit of his (the first I have a clear memory of), that I had two daddies, ‘Daddy Greg’ and ‘Daddy Tony’, so wasn’t I a lucky child? Years later, she told me that I had sulked and muttered, ‘I only want one daddy, Daddy Greg.’ That part, I don’t remember. I do remember, though, her telling me that it was up to me how I wanted to call ‘Daddy Tony’ and ‘Daddy Greg’, which smacked of pressuring me a bit into calling my father ‘Daddy’. If subtle pressure was intended, it did not work. I made up my mind then and there not to call my father ‘Dad’ and stuck to my decision: Greg I would always call ‘Dad’; my father I chose to call Tony. I still call him Tony, although, recently, I have found myself calling him ‘Dad’ a couple of times, feeling, afterwards, a tad disloyal towards Greg about that. Greg died of a heart attack a couple of years ago, and my mother of cancer five years earlier.

I believe that my father was quite content with my calling him Tony. In any case, he never showed any wish for me to call him ‘Dad’ or ‘Daddy’. As a child, then as an adolescent, I got used to his distant presence in my life. I thought of him as a benevolent and somewhat peculiar uncle. For his part, he never tried to force himself into my life or demand any special marks of consideration from me, which was a relief, because I was very attached to Greg and did not want to seem to be changing allegiances.

Even when I was a little boy my father interacted with me as though I was an adult. That very first time I remember him visiting us he talked to me in a way that made my mother laugh and tell him, ‘Hey Tony, the boy’s not even in first grade.’ It would take me a little while to get used to my father’s English. Besides the fact that he used many words that were beyond a child’s comprehension, he spoke English with a bit of an accent. It took me even longer to adjust to his social manner. He seemed either lost in thought and remote, or was, on the contrary, very present, commanding everybody’s attention by firing off one idea after the next. He would talk mostly about ideas, hardly ever about anything concrete, tangible or personal, and he could get quite vehement. Much more vehement than any of the other adults who visited us, even though, unlike them, he never touched a drop of liquor. At first, his vehemence made me uneasy, even frightened. But then, observing that the other adults seemed to enjoy listening to him, I grew more comfortable with his style.

Once, he came to see us in the company of a woman, Maria. ‘She is a staunch feminist,’ he told my mother. In my early teens at the time of this visit, I was curious to see the woman for whom my father felt strongly enough to travel with. I did not know what to expect, as I had never seen him with a woman. Her being a staunch feminist heightened my curiosity. She turned out to be dainty and reserved. She was remarkably quiet throughout the weekend they spent with us. We never got to hear her views – feminist or otherwise. She was significantly younger than him, by then in his mid-forties. He seemed attentive to her every need as well as unsure of himself, unsure of how to behave in her presence. A day after they had been with us, I overheard my mother tell Greg, ‘I sure hope it works. It’s difficult for me to form an impression of her.’ It did not work. We heard a few months later that Maria had decided that life with him was too austere. That was what he wrote on a card he sent us, adding in a post scriptum, ‘Of course, she is right, but there’s not much I can do about it!’ My mother was upset for him. Greg suggested that he was perhaps happy on his own. ‘He has no one,’ my mother lamented, ‘no brothers, no sisters, no father, no mother, no cousins he is in contact with. Just us, and we’re miles away.’

Over the years, we paid him a few visits – once in New York, twice in Paris and twice in London. It did not matter where he lived, his place – always in the heart of the city – looked the same. A studio apartment littered with books and papers and with hardly any furniture to speak of. It is only relatively late in life that he acquired a computer and started collecting tapes and CDs, at which point he bought himself a rather fancy stereo system, after innumerable long distance telephone conversations with Greg about which kind to get.

Besides Maria, I never heard of another woman in his life, although he did have a couple of women friends who seemed quite fond of him. So my mother was not entirely correct when she said that he could count on no one but us. But, yes, he had no family and no partner, which is what prompted her to tell me, after she found out about her terminal cancer, to keep an eye on him; and to look after him the day he needed to be looked after. She wrote me a letter saying that. And told Greg to re-convey the message after she died.

My father was with us during the last days of my mother’s life. I could not tell how he felt until the funeral when, all of a sudden, he seemed very distraught – he burst out sobbing – and Greg had to console him.

When Greg died, my father called me from London to say that he would not come to the service, that he would find it too hard. It is the one and only time he said something to me about his feelings. He was born in Alexandria in 1933. He spoke freely of his family background, but gave only the dry facts, never dwelling on what it had meant for him to have grown up in a world which, from all I heard about Alexandria of the thirties and forties, must have been a rather special place. Once, I tried to make him talk about that Alexandria, and he said, ‘Paris [my mother thought that Greek name beautiful, and Paris was where she had met my father], what should I tell you? It’s not as if I don’t want to talk about it. But anything I can think of saying is trite. Should I be telling you that I loved to hang around the harbour and Ramleh Station, that I felt at home in the maze-like, seedy old Turkish Town, that, along parts of the Corniche, the smell of the sea and of fish could be overpowering; that the sunsets were beautiful; that many languages were spoken, often in a curious mishmash? All this has been said before by others much better than I could say it. And the truth is that, over the years, that part of my life – that world – has lost its reality for me. It has become a bit like a mirage. I can’t feel it or smell it any longer. It’s gone, very much gone. Some people look back. I’m not one of them.’

Of his Alexandrian origins, he told us that his father, a small grocery store owner, moved there in the early 1920s from a town in the Delta, where the grandfather had set up shop, using his teenage sons as helpers. I don’t know how long the family had lived in that town before Tony’s father moved to Alexandria at a time when apparently many Greek shopkeepers were leaving the Egyptian countryside and smaller towns. Hard times for cotton traders and their agents were hurting their business. They were hoping to do better in the big cities. Tony’s father had always dreamed of living by the sea, and so chose to try his luck in Alexandria and, with borrowed money, he opened a tiny grocery store, renting an adjoining flat. The store and flat were in a poor part of the city. The father’s only brother found himself a job in the canal industry, in S

uez, and became a union organiser, which quickly became a subject of dissension between the two brothers, for Tony’s father disliked unions. Another thorny subject between them was Tony’s father marrying Tony’s mother, a White Russian. The brother frowned upon that union; rarely did Greeks in Egypt, at the time, marry non-Greeks. The relationship between the two brothers worsened. That Tony’s mother came from a solidly bourgeois background did not help. Her father had been a pharmacist in Kiev. She had fled Russia in her early twenties, going first to Istanbul, then to Alexandria. Tony was the couple’s only child. His mother hardly ever set foot in the grocery store, of which he, however, has fond memories, perhaps, he said, because his father had never required him to work in it. His mother gave piano and French lessons and did embroidery piecework. ‘Serious’ is how Tony described her, whereas his father, he told us, had been a bubbly sort. When his father died of a heart attack and Tony was in his early teens, his mother sold the store and would have nothing to do with her brother-in-law, fearing that he would try to claim some sort of guardianship over Tony. She need not have worried, for the uncle left mother and son in peace. Luckily, she found a supervisory job in an embroidery workshop and managed to support herself and her son. Tony’s life was not turned upside down by his father’s death. Even though she sold the store, his mother kept the adjoining apartment, which remained their home. And he continued to attend the same Greek school – a school funded by the Greek community. When it became obvious that he had a special gift for languages, a rich benefactor (one of the co-owners of the embroidery workshop) offered to put him through university abroad. It was the early fifties. He went to Paris, where his mother had some distant relatives with whom he could stay for a while. A year later, his mother followed him to Paris. He lived with one set of her relatives, and she with another. Less than a year after her arrival, she died of a stroke. He had just turned twenty. He never went back to Egypt. His uncle left Egypt in the late fifties and emigrated to Australia.

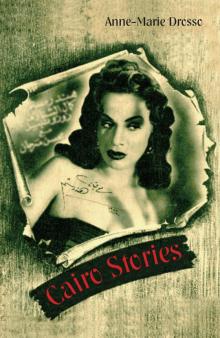

Cairo Stories

Cairo Stories